The name of the beer is Toast. And like the kvasses that have recently emerged stateside, Toast drives home the epigram of “liquid bread” by using the starchy sugars from bread to fuel beer fermentation.

“What’s different about kvass versus what we’re doing with Toast is that we’re seeing bread as something that has the same fundamental element of other grains, long-chain carbohydrates for brewing,” says Madi Holtzman, the USA director for Toast Ale, a company that only makes beers derived from a mash bill with roughly 30 percent rescued bread content.

Celebrity chef Jamie Oliver, who tried Toast Ale on his show Friday Night Feast, called the stuff “bloomin’ good.”

Kvass (pronounced “quass”) isn’t the only beer style to use bread, though it might have put the idea on the modern radar. As this magazine has published in the past, kvass isn’t strictly beer but rather a traditional Eastern European drink that brewers have reimagined into a beer style. Historically, it involved fermenting leftover rye bread using wild microorganisms and occasional adjuncts to stretch bread’s caloric usefulness into a tasty, low-alcohol and tart beverage. Modern brewers use additional malt to beef up the alcohol content and make it beer, though most kvasses, like those from Jester King Brewery and Fonta Flora Brewery, still hover around 2-4% ABV.

The zeitgeist of imagination that produced kvass’ reinterpretation into beer style has also pushed Toast Ale and a similar slew of brewers to use bread outside of kvass’ stylistic boundaries. In Toast’s case, founder Tristram Stuart first tried a bread-based English bitter at the Brussels Beer Project, then launched his U.K.-based company in January 2016. Toast has since produced a Craft Lager, Lovely Session IPA and Purebread Pale Ale in the U.K. with bread, and recently launched in the USA with a flagship American Pale Ale. It also produces a series of bread-based collaboration brews on both sides of the Atlantic.

“Tristram just totally had a lightbulb moment,” says Holtzman, noting that Stuart has worked in food recovery for years and has long been aware of the massive amount of food the globe wastes annually (the United States wastes 30-40 percent of the food it produces, according to the United States Department of Agriculture). Bread is a major culprit in this issue. Around 24 million slices are wasted each day in the United Kingdom, according to the U.K.-based Waste & Resource Actions Programme.

“I think that him not being somebody with any background or experience in the beer world, his [Stuart’s] mind automatically jumped to an imaginative place,” she continues. A similar surplus-beer-to-bread project has also been performed, sporadically, by East End Brewing Co. and 412 Food Rescue in Pittsburgh (the first batch was an IPA and a second batch is expected to go into fermentors this fall).

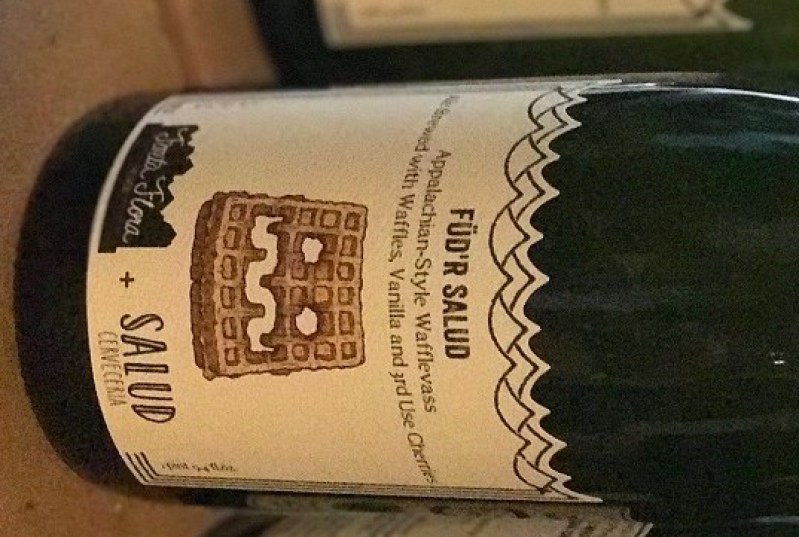

Beyond the inspiration of outside business experience, other brewers, too, have found that imaginative sweet spot to link beer and bread in novel ways. This year at Salud Cervecería in Charlotte, North Carolina, owner Jason Glunt partnered with Fonta Flora Brewery’s Todd Boera to brew a waffle kvass after releasing a special imperial waffle stout—in raspberry (Frambella) and S’mores forms—in 2016.

The collaboration kvass incorporated cherries and vanilla “to break it up a little bit—it had a slight tartness, but not overwhelming,” Glunt says.

Waffle flavor wasn’t very present in the kvass, according to Glunt, but he points out that the waffles used to make that beer were rye waffles and “definitely not waffles you would want to eat.” For Salud’s waffle stout, on the other hand, the waffles (made regularly at FūD at Salud) gave the beer a rich mouthfeel and a “bready, waffle-type flavor.”

“They were both received well,” he continues. “We sold out 20 cases in an hour for the collaboration with Fonta Flora.”

At the waffle stout’s 2016 release party, the entire 31-gallon batch “pretty much kicked” the day of the event.

Virginia’s Devils Backbone Brewing Co. also forayed into the field of bready stouts with its Seven Summits imperial stout, one of a dozen beers included in the brewery’s Adventure Pack last year. Inspired by the climbing pastime of collaboration brewer Walt Dickinson (co-founder of Wicked Weed Brewing Co.), the beer comprised ingredients from seven summits across the world. For the Caucasus Mountains and Mount Elbrus, rye bread and the kvasses it occasionally finds its way into were sources of inspiration.

“This is a big beer, so this is probably as far away from a kvass as you can be,” says Jason Oliver, founding brewmaster at Devils Backbone. But, in his case, the complexity of the imperial stout style in addition to the vast bill of adjuncts—coconut, cocoa, blue-green algae, American oak, pink Himalayan sea salt, and wattleseeds—overwhelmed any bready presence.

“To be honest with you, you’d probably be hard pressed, if you didn’t know there was bread in there, to figure it out,” he says.

“Not to get cliché but, the total was greater than the sum of all its parts,” he continues. “Not any one of those components stuck out in an obtuse way and they all came together to form a complex and reflective beer.”

Oliver figures the company brewed roughly 480 barrels of Seven Summits, using about half a pound of bread per barrel. Oliver also says that Devils Backbone currently has a kvass and kombucha hybrid “on the radar.” Elysian Brewing Co. in Washington, too, is about to unveil a kvass, a “Crust-Punk” pumpkin one brewed with sourdough rye bread, malted rye, pumpkin and pumpkin seeds (the brewery is known for its range of pumpkin beers and the Great Pumpkin Beer Festival, for which this kvass was brewed).

“In terms of seeds, brewers have been shy about using any type because we feared the oils would kill the head retention,” says Josh Waldman, head brewer at Elysian Brewing Co. “We learned that seeds don’t affect the quality of beers like we thought they did.”

Holtzman says that Toast Ale’s beers, like Seven Summits and Salud’s collaboration kvass, are similarly subtle in their bread contents, with perhaps a slight caramel overtone revealing the ingredient (though a tasting panel of chefs and brewers, she says, struggled to detect bread in the beer). Other brewers I spoke to who work with bread in off-kilter styles—such as Dimitri Van Roy at Brussels Beer Co.—also acknowledged this subtle caramel note that bread can lend, and some, too, spoke of a slight presence of salinity. Most said that overall the impact is minuscule—if at all noticeable.

Toast is currently contract brewing out of Chelsea Craft Brewing Co. in the Bronx, New York, for its U.S. production. Only the American Pale Ale, produced stateside, is available domestically for the sake of sustainability. As of this writing, the brewery has produced 105 barrels of beer and is only available in New York, but expects to expand “four-fold” over the next year and is on on the lookout for a new consulting brewer to help with expansion. The brewery hopes that its business serves as both proof and model for other breweries to tap into the vast unused source of sugars—and in turn, beer—that can be found in wasted bread.

Toast Ale will be hosting an open-to-the-public collaboration release with La Birreria, Eataly’s rooftop bar and microbrewery, at its Flatiron location in New York City, on Sept. 21.